The Birds

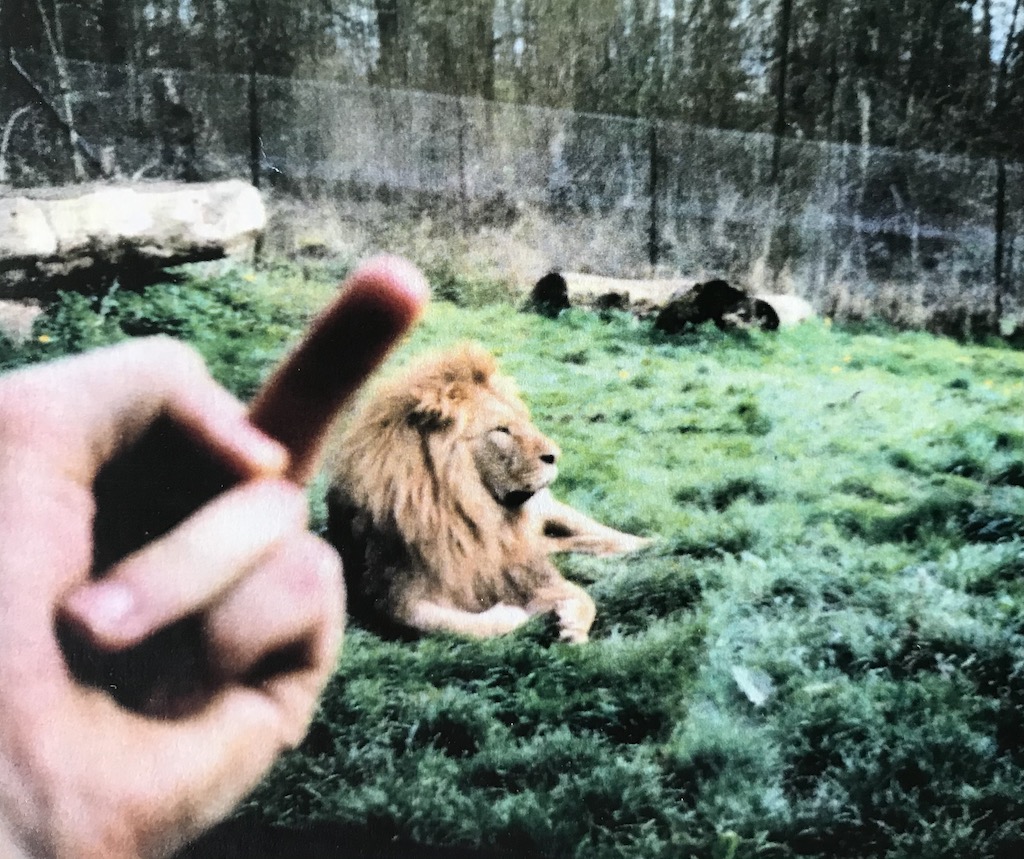

It was probably around 1988, when aged 17, some friends and I took a trip to Longleat Safari Park in the Southwest of England. During our drive through the animal enclosures I felt compelled to take a photo of a recumbent male lion.

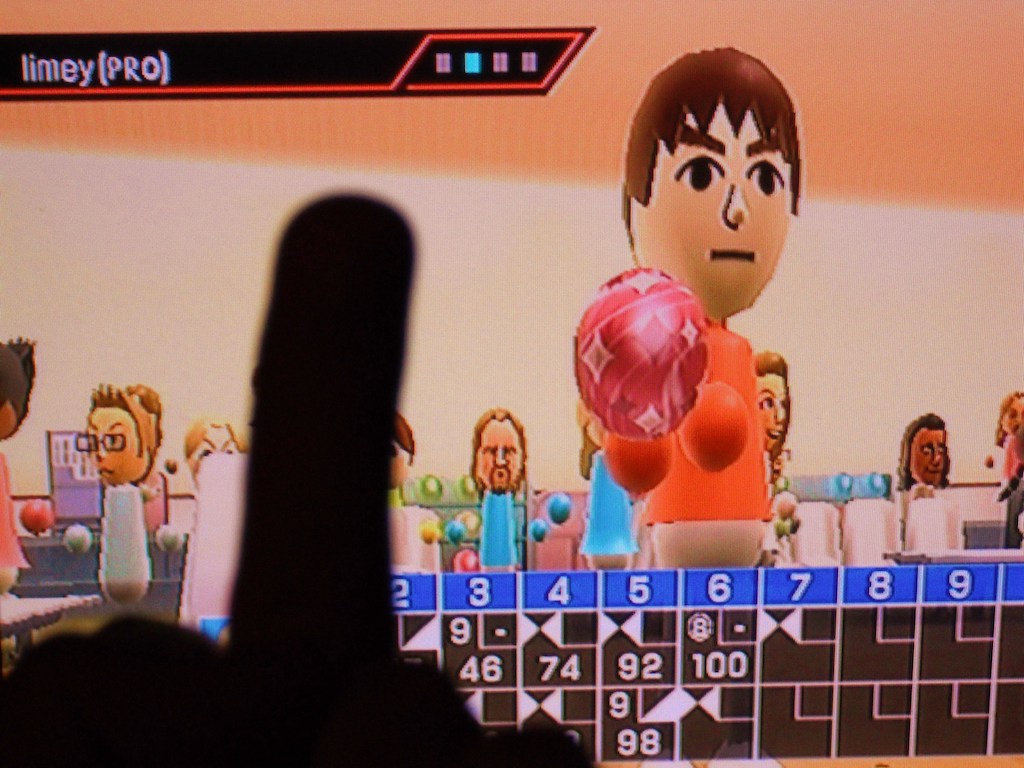

However, the impulse to place my middle finger, known in certain quarters as “The Bird,” was overwhelming. So I took aim and shot. I was a chickenshit Hemingway on a cowardly drive-by some might say.

The cat remained nonplussed, but I became giddy with ‘the giggles,’ and a photographic leitmotif was born. For the foreseeable future I would ‘flick-n-click’ whenever appropriateness was in doubt.

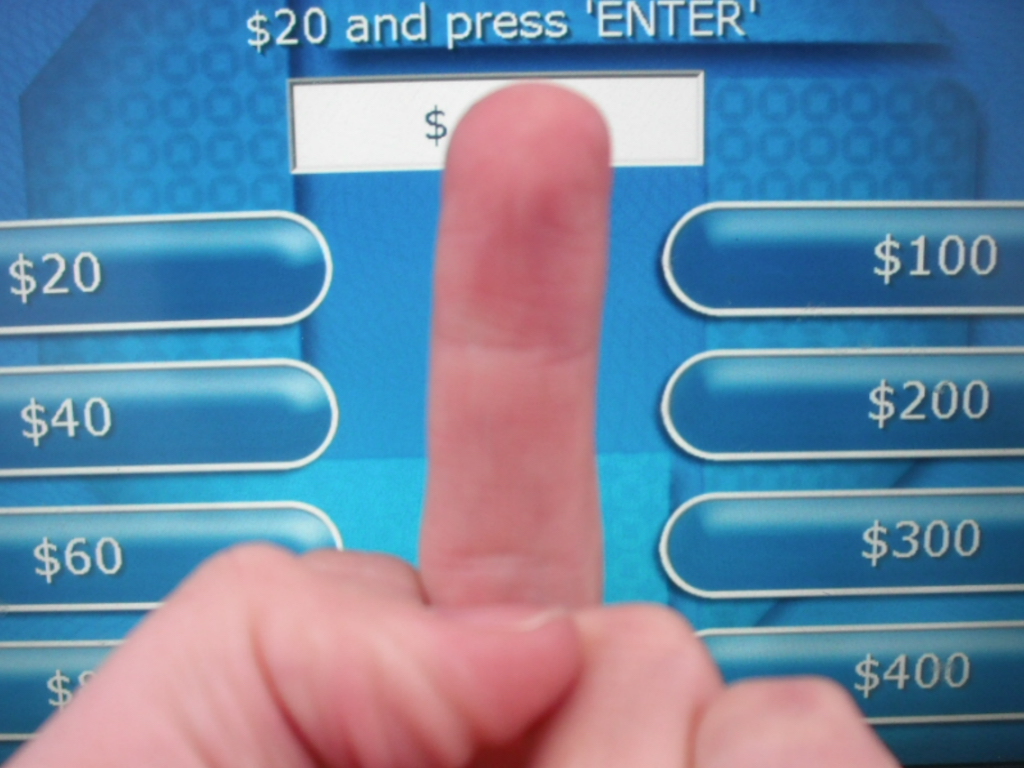

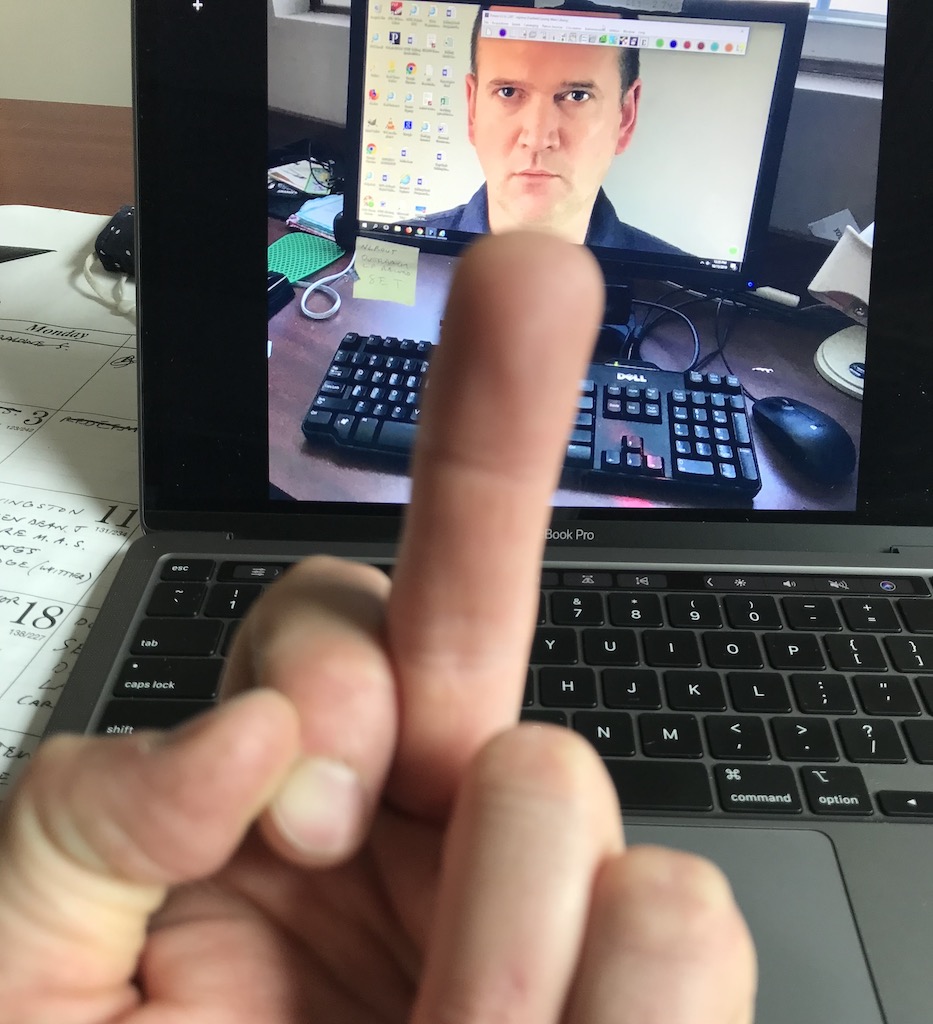

The middle finger gesture is used as a visual probe which occupies a no-man’s land between lens and subject. The viewer is invited to assume the role of perpetrator as the finger enters the frame from the camera’s perspective.

In The Birds, the photographer delivers the gesture, rather than say, a finger being aimed at the camera from the subject’s side. Think of the typical celebrity, flustered by paparazzi, flicking the middle finger at the lens. However, the viewer is now promoted to the job of assistant aesthetic antagonist, no longer passive in surveying a range visual material.

The bird gesture is perhaps a cultural form which symbolizes new world modernism in the American tradition: Sleek, economical, minimal and ‘in-your-face.’ The finger is also a conductor, in this case, of images, a formal component in the picture which highlights spatial proximity.

As the finger is now seen from ‘the wrong side,’ the gesture seems to soften and becomes a more ambiguous prompt in reconsidering the subject. Confrontation shifts from a raw inarticulate expression of anger to a more nuanced dialogue; a nice chat with the picture-to-be.

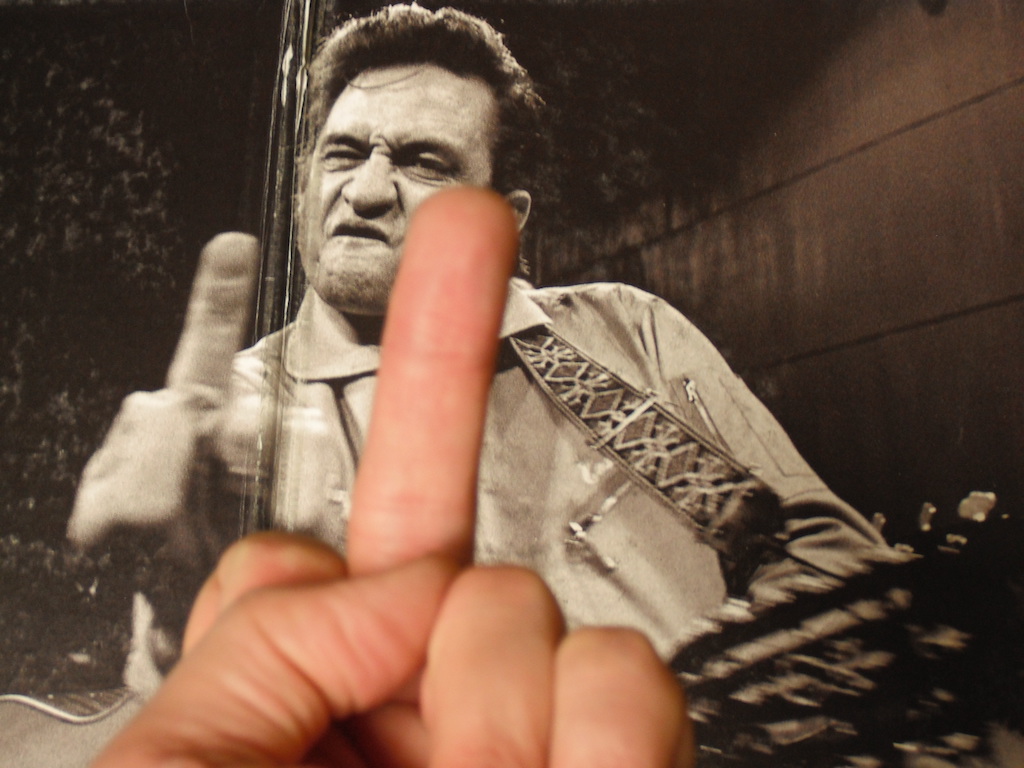

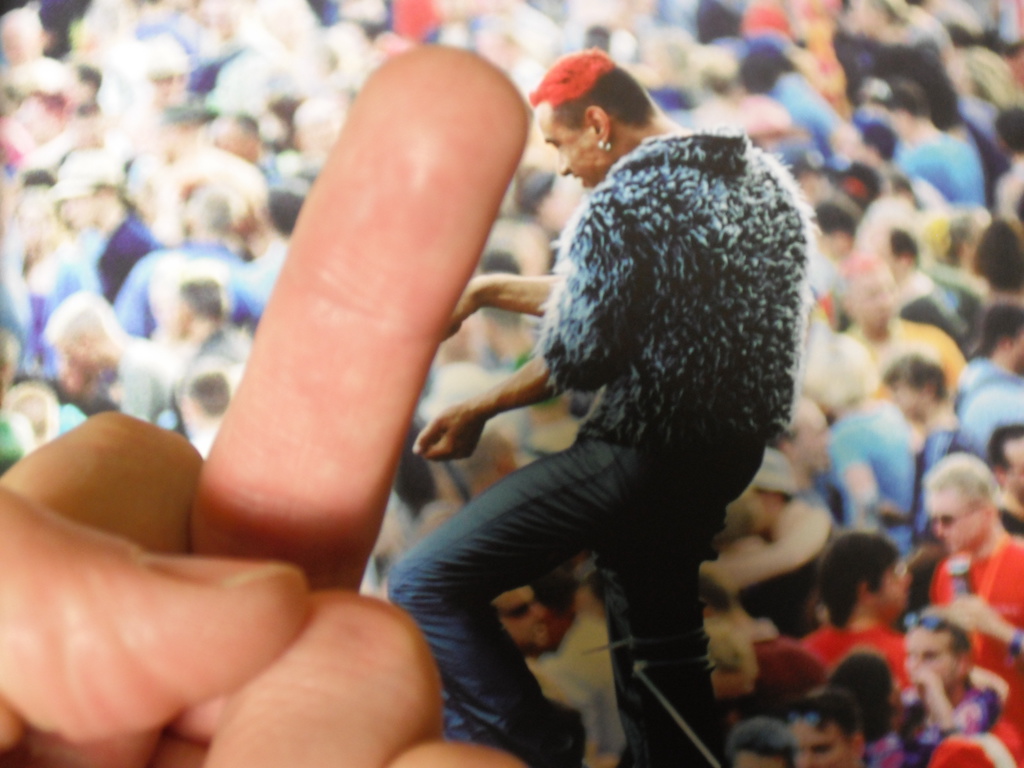

Some of the photographs are taken “live” in-situ, and emphasize ‘the moment’ while other images are appropriated from books and magazines and incorporate various lighting and spatial set-ups, Real life subjects, screens, book pages and other flat surfaces. When taking ‘live’ photographs one is mindful of being observed; the act of photography is dramatized by my prominent vertical digit and taking the photo becomes a kind of performance, the finger speedily placed in the frame as the button is pressed. Bystanders could indeed succumb to ‘friendly fire,’ or misinterpret artistic procedure as outright belligerence. “Sorry Madam! Must dash!

This project aims to question the physical, confrontational role of the photographer on-the-job, and of how we live with and use images that are not only made by us as individuals, but of pictures inflicted on our experience by more sinister agency.

Across the frames, the finger acquires a form reminiscent of the human figure: It becomes a limbless and featureless character.

The finger appears as confrontational, inquisitive and even sympathetic; as seen in the image below, the finger rests against the page and points to Marx’s title, having patiently digested his ideas as the author’s ghost peers through the book cover.